Legend has it that the Chinese Empress Leizu was sitting in the shade of a mulberry tree when she saw a little cocoon fall into her cup of hot tea. As she picked it up, she noticed that it unravelled into a fine thread. She unwound the string and was intrigued by how long and strong it seemed to be. Her husband, the emperor, designed the first loom and planted more mulberry trees. Unsurprisingly, this rich fabric was exclusively made by women and reserved for the upper echelons of Chinese royalty for hundreds of years. It remained China’s best-kept secret for a thousand years, until a Buddhist monk was brave and kind enough to bring silk to India during the Gupta period.

Today, India stands second to China in silk production, with only a few states engaged in weaving this exquisite fabric. The story we’ve brought to you this week is from a start-up, Serigreen Technologies, incubated at IIT Madras, aiming to transform sericulture through technology. Co-founded by Vennila Shanmugakumar and Venkatesh, Serigreen works with farmers to increase mulberry yield, monitor silkworm health, reduce worm mortality, and make sericulture a viable, year-round livelihood.

From soil to silk, the co-founders, their team, and their mentors bring solutions using technology that’s based entirely on farmer feedback and research.

For co-founders Venkatesh and Vennila, the silk industry is not new. Venkatesh comes from generations of mulberry tree farmers. Vennila has grown up watching her father build Murugappa Silks from six hand looms to one of the leading silk saree weavers and retailers in Selam. “Today, my father has brought it up to 400 hand looms and 100+ power looms, and they export sarees across the world,” explains Vennila.

Behind the scenes

Behind the scenes

However, with the pandemic, imports of raw silk from China were disrupted, and the weavers suffered. It brought a pause to the supply chain when all imports from China were banned. ‘Why can’t we produce the same quality silk here in India? Why do we have to depend only on China’s raw silk?’ wondered Vennila. She dug deep to the root of the problem: the quantity and quality of the thread depends on the quality of the cocoons, which is traced back to the quality of care and feed the worms get, which is affected by the quality of the mulberry trees and the soil they grow in!

Vennila and her co-founder Venkatesh, who was an energy auditor at CII, Bangalore, began to explore ways to bridge this gap. Venkatesh brought in-depth knowledge of mulberry farms and the process of sericulture and pointed out the various challenges the farmers faced. “One discovery we made was that in agriculture, India has seen so much progress due to technology.

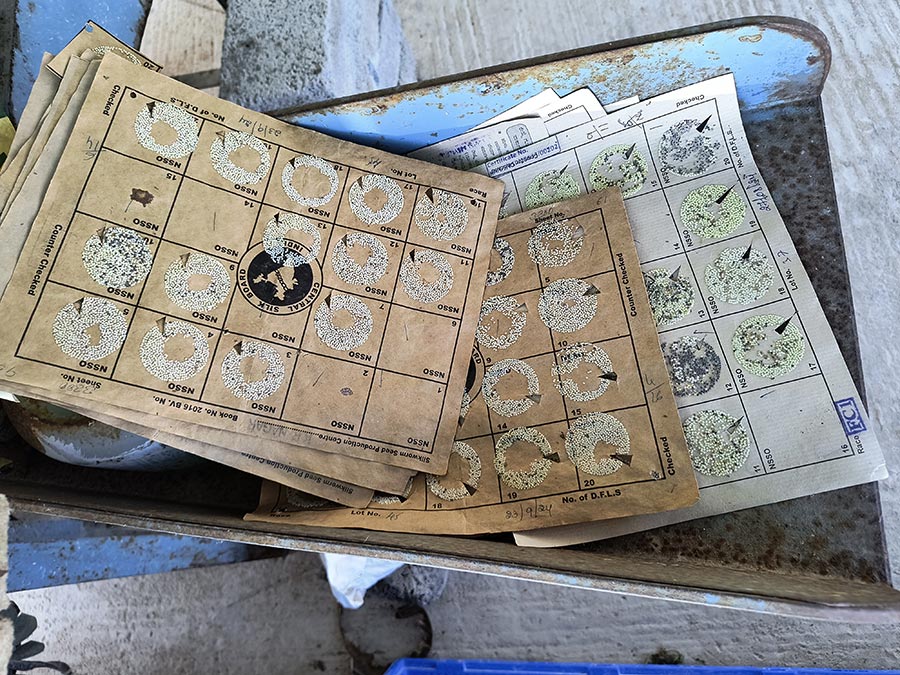

Glimpses of the silkworm production seed centre

Glimpses of the silkworm production seed centre

However, in sericulture, technology didn’t seem to play a role at any stage at all. There’s no automation, and therefore no opportunity to upgrade processes at all. There was definitely an opportunity here!” exclaims Vennila.

Piles of spun silk, akin to the first ever Chinese cocoon story

Piles of spun silk, akin to the first ever Chinese cocoon story

Vennila says, “I was shocked when I discovered that farmers in sericulture can actually earn money virtually every month of the year—unlike in agriculture, which depends on the seasons. Why then, do people hesitate to enter this industry despite these possibilities?” The answer, as they say, was blowing in the wind. She lists a host of reasons for the hurdles, starting with the very picky caterpillars. Once the eggs hatch, they start feeding exclusively on mulberry leaves; they do not survive on any other plant or leaf. Another condition for their uninterrupted feeding: climatic conditions between 23-28 degrees temperature and 65-90 per cent humidity. Therefore, only select areas in Tamil Nadu, Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka, Maharashtra and a few places in North India fulfil these conditions. In Tamil Nadu, Coimbatore, Selam, Karur, Namakkal, Pollachi, and Dindigul have conducive conditions.

Farmers maintaining optimum mulberry crops for the caterpillars

Farmers maintaining optimum mulberry crops for the caterpillars

Vennila continues, “So how do we counter the risk factor and increase quality and quantity? We saw an untapped opportunity in bringing tech to sericulture. My husband and I discussed this with Venkatesh, whose family was involved in sericulture for more than four decades. He was on board immediately. By then, I had received funds from Pravarthaka, a funding agency in IIT, Madras. I am a computer Science graduate, and there is no connection with the work I do,” laughs Vennila. “My husband helped us find an office in IIT Madras, and we moved there from Selam, for our start-up. Our mission was simple: to reach the right people at the right time with the right solution. To reach the farmers and educate them on technology, we had to go back to the soil. We met more than a hundred farmers in the area and learned the process thoroughly.”

Mulberry trees grow in a specific kind of soil: they do not require pesticides, though the soil has to be fertile. The leaves on the shoots are harvested and taken to a special shed where the worms are housed. Receiving eggs from the government is contingent on the farmer owning at least an acre of land. The agencies hand out small worms and/or eggs on patches, which are placed in cubes inside these sheds. Once these eggs hatch, the worms begin to feed on bundles of mulberry leaves and grow rapidly in the next two weeks, when they are ready to spin their cocoons. These are then delivered to the auction centres, which are also run by the government.

Sericulture farmers receive both state and central subsidies from the soil to the cocoon stages. However, in this supply chain, there are a number of obstacles: the worms feed exclusively and entirely on mulberry leaves—they do not even consume water. If their leaves are contaminated, they stop feeding. They have to be fed only with fresh-cut leaves. If the freshness decreases even a little, the worms reject them. “Such a sophisticated fellow, our silkworm!” chuckles Vennila.

“They have to be fed every six hours! And throughout this process, there is no technology to support the farmers in any of these delicate stages.”

Quality checks

Quality checks

Vennila and Venkatesh talked to people who were involved in each of these stages. The government agencies that supply the eggs, the ‘late-age rearing’ farmers, the people who reel in the silk from the cocoon, the buyer, the weaver, and, of course, the retailer. Finally, it was clear that they had to go back to the soil. “If we started by finding a solution there, we could work our way up,” explains Vennila. “So, we chose to work with the late-age farmers who are the ones directly in touch with the roots. The issue they faced was their inability to maintain temperatures in their worm sheds, which meant that they could rear silkworms only six months of the year. The rest of the time, either the humidity or the temperatures are not conducive. Currently, they use basic practices like burning coal in pots to heat the sheds, but they are obviously ineffective and unsustainable.”

Serigreen began with building a pilot in Sathyamangalam to compare silkworm rearing under test conditions. They have achieved a 5 -10% increase in production. Vennila adds, “It’s not much, but we do know that it is a more effective solution to keeping the silkworms in optimum conditions.” The team also tackled pesticide drift, a major cause of worm mortality. “Serigreen’s IoT-based sensors sense pesticides that invade the air around the mulberry trees and warn the farmer, who then can wash the leaves before harvesting them for the worms. The IoT device is highly sensitive to any kind of sediment that’s deposited on the leaves, so the purity of the feed is maintained,” explains Vennila. Lab testing is ongoing, and they have now installed the devices in farms that can afford it. “Our goal is to make these technologies effective and affordable,” says Vennila. “When farmers can trust the process, we’ll see fewer failures and higher-quality silk threads.”

Serigreen is funded by MaDeIT, an incubation fund of the Indian Institute of Technology Design and Manufacturing Kancheepuram, in Vandalur, a branch of the Ministry of Human Resource Development, Government of India. The company also receives funds from IIT Madras – Pravartak.

“We have great mentors and a great team,” says Vennila. “Mr Prabhakar, a veteran sericulture scientist, and Mr Shanmugakumar, our strategic advisor, have guided us all through our start-up journey. Our technical officer is Mr Bhargav, who began as an intern and is now fully employed at Serigreen. And our structural engineer is Mrs Mahalakshmi, who has been with us for many years now.”

“Our journey has been deeply collaborative,” says Vennila. “We design all our products in-house, prototype and test them in our labs, and validate them through pilot studies in real farms,” says Vennila. Our journey has been enriching and interesting so far. Whether Serigreen will be an agritech company or a biotech company, or both, only time will tell,” she smiles.

Passionate, committed, and eager to ensure better quality, better quantity and 100% waste to wealth for sericulture farmers, is the vision of the co-founders of Serigreen, Vennila and Venkatesh.

Empress Leizu will be proud, no doubt, of this story of silken threads.

For further details, check the Serigreen website www.serigreen.in

When this story reaches 1000 views we will cover an exclusive of this business.